The Harvard course “Introduction to the Mathematical Treatment of Economic Theory” (Economics 8a from 1934-35 to 1935-36 then renumbered as Economics 4a thereon through 1940-41) was taught by Wassily Leontief except for its very first year when Joseph Schumpeter was responsible for the course. The original handwritten draft of the final examination for February 4, 1935 can be found in Schumpeter’s papers (though filed along with papers for the other course he taught, Economics 11). The official typed draft of the exam (identical except for a line-break) is transcribed below along with information about the course enrollment and prerequisites.

_____________________________

Course Announcement

Economics 8a 1hf. Introduction to the Mathematical Treatment of Economic Theory

Half-course (first half-year). Mon., 4 to 6, and a third hour (at the pleasure of the instructor). Professor Schumpeter.

Economics A and Mathematics A, or their equivalents, are prerequisites for this course.

Source: Announcement of the Courses of Instruction Offered by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences During 1934-35 (Second Edition) published in Official Register of Harvard University, Vol. XXXI, No. 38 (September 20, 1934), p. 126.

_____________________________

Course Enrollment

[Economics] 8a 1hf. Professor Schumpeter and other members of the Department.—Introduction to the Mathematical Treatment of Economic Theory.

Total 23: 15 Graduates, 3 Seniors, 5 Instructors.

Source: Harvard University. Report of the President of Harvard College 1933-34, p. 85.

_____________________________

Final Examination

Introduction to the Mathematical Treatment of Economic Theory

Joseph A. Schumpeter

1934-35

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

ECONOMICS 8a1

Answer at least THREE of the following questions:

- Define elasticity of demand, and deduce that demand function, which corresponds to a constant coefficient of elasticity.

- Let D be quantity demanded, p price, and D = a – bp the demand function. Assume there are no costs of production. Then the price p0 which will maximize monopoly-revenue is equal to one half of that price p1, at which D would vanish. Prove.

- A product P is being produced by two factors of production L and C. The production-function is P = bLkC1-k , b and k being constants. Calculate the marginal degrees of productivity of L and C, and show that remuneration of factors according to the marginal productivity principle will in this case just exhaust the product.

- In perfect competition equilibrium price is equal to marginal costs. Prove this proposition and work it out for the special case of the total cost function

y = a + bx, y being total cost, x quantity produced, and a and b

- If y be the satisfaction which a person derives from an income x, and if we assume (following Bernoulli) that the increase of satisfaction which he derives from an addition of one per cent to his income, is the same whatever the amount of the income, we have dy/dx = constant/x. Find y.

Should an income tax be proportional to income, or progressive or regressive, if Bernoulli’s hypothesis is assumed to be correct, and if the tax is to inflict equal sacrifice on everyone?

Final. 1935.

[Handwritten note at the bottom of this carbon-copy of the exam questions: “This leads me to believe that the course is advantageous only if the man has had previous mathematical training at least equal to Mat A”]

Source: Harvard University Archives. Harvard University. Final Examinations, 1853-2001 (HUC 7000.28, Box 15 of 284). Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Papers Printed for Final Examinations: History, History of Religions, … , Economics, … , Military Science, Naval Science, January, 1948.

_____________________________

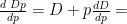

Schumpeter’s handwritten answer to question 2

[Note: Schumpeter’s draft of his questions for Economics 8a in 1934-35 were incorrectly filed in the Economics 11 course folder for the Fall semester of 1935. Perhaps he used the questions himself in the other course in the following semester.]

Source: Harvard University Archives. Joseph Schumpeter Lecture Notes. Box 9, Folder “Ec 11 Fall 1935”.

Image Source: Joseph A. Schumpeter’s note at the end of his handwritten draft of the examination in Harvard University Archives. Joseph Schumpeter Lecture Notes. Box 9, Folder “Ec 11 Fall 1935”.